Copyright - Temp Tracks in Film Music

- Yasmin Amir Hamzah

- Apr 11, 2018

- 3 min read

At first glance, copyright can seem like quite the boring subject – I mean, contracts and paperwork, this is stuff for lawyers, right? Well, not exactly. More than anyone else, it is most important that artists and other people who work in the creative industries understand the legalities around copyright, how to apply it to our works, and above all how to avoid breaching it in the things we create. But if a work manages to stay within the limits of copyright, does this still mean that it is ‘original’?

In 2016, Brian Satterwhite, Taylor Ramos, and Tony Zhou published an audio-visual essay onto Youtube (The Marvel Symphonic Universe), discussing the memorable qualities – or lack therof – in the music of the Marvel cinematic universe. They also discuss the use of temp music in modern day films, and the shocking similarities between Hollywood movies as a result.

(start at 5:49)

(Satterwhite, B., Ramos, T., & Zhou, T. (2016). The Marvel Symphonic Universe)

So what is temp music?

Temp music, or a ‘temp track’, refers to a piece of music that a film director uses as a placeholder during the editing process. The purpose of the temp acts as a guide to both the editors and the directors to help shape the emotion and focus of the scene in terms of camera angles and perspective. In some cases they can even help the composer understand what the directors want from a soundtrack.

So why is this a problem?

Well, logistically it isn’t – the use of temp music is 100% legal, since the borrowed music shouldn’t ever make it into the finished film (in unique cases like 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick & Clarke, 1968), the classical music that was used was done so with permission). But, does this pose a problem by limiting the creativity of today’s filmmakers?

In the last several decades of filmmaking, many directors seem to show a heavier reliance on temp music when giving direction for their scores. As a result, in today’s Hollywood we are seeing many films that have music that sound very similar – in some cases almost identical – to one another, imitating each other just within legal limits, dancing the line between inspiration and plagiarism.

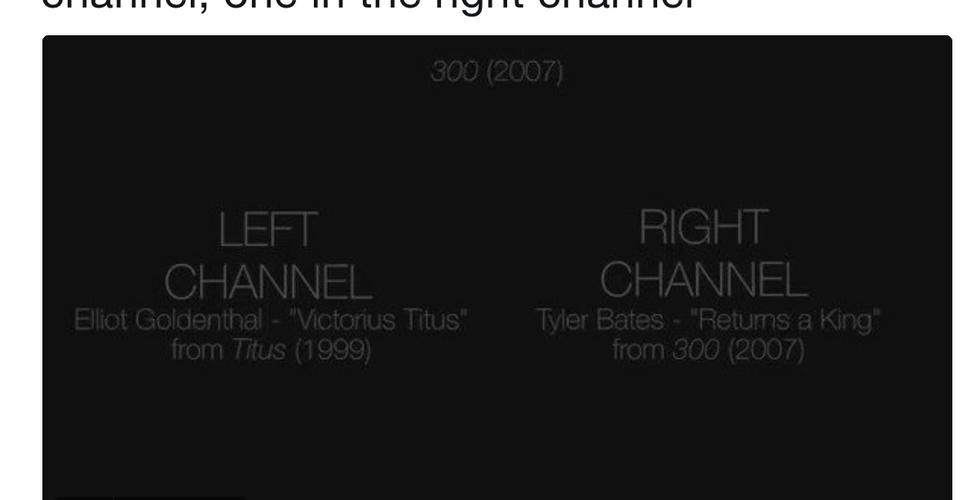

Some examples can be seen on the twitter page Sounds Like Temp, which is run by the same Tony Zhou (2016), and shows movie scenes back to back comparing the temp music to the composed soundtrack.

Satterwhite, Ramos, and Zhou argue that the trend of composers imitating temp music is detrimental to the film industry, and can lead to film music being unmemorable, ‘safe’, and lacking in emotion (11:29 minutes). This is an opinion that I tend to agree with, and if nothing else, the use of temp music promotes an unhealthy cycle between filmmakers and composers, discouraging the motivation for each to learn about the other’s respective art.

Above all, the use of temp music limits the creative borders of film music, especially if filmmakers recycle through the same style of temp music. For example, most Hollywood movies have recently chose to muse music from big flicks such as Transformers (Bay, 2011) or the Bourne Legacy (Liman, 2002) for generic action scene music, which was highlighted in a response to the Marvel Symphonic Universe essay by Dan Golding (A Theory of Film Music, 2015). The response also highlights that main purpose of film scoring is not to be creative, but to guide the watcher, especially in the scope of communicating the film’s ideas and moods to the less intelligent members of the audience.

Golding, D. (2015). A Theory of Film Music. YouTube.

So, to conclude the discussions from both these essays on temp music, it can be said that while film music was originally a directive tool in film and not a creative one, there is still room for composers to write bold and unique music, and film scoring can and should be used as way to make movies memorable and special.

This is an attitude that I hope to take in my practise, both long and short-term, in the gaming scores that I am currently composing, and in the future films that I will hopefully be a part of.

Works Cited

Bay, M. (Director). (2011). Transformers: Dark of the Moon [Motion Picture].

Golding, D. (2015). A Theory of Film Music. YouTube.

Kubrick, S., Clarke, A. (Writers), & Kubrick, S. (Director). (1968). 2001: A Space Odyssey [Motion Picture].

Liman, D. (Director). (2002). The Bourne Identity [Motion Picture].

Satterwhite, B., Ramos, T., & Zhou, T. (2016). The Marvel Symphonic Universe. Vancouver: YouTube.

Zhou, T. (2016, August). Sounds Like Temp. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from Twitter: https://twitter.com/SoundsLikeTemp

Comments